STILL garments

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, fabric was crafted or woven by hand, making it a luxury product, only available in larger quantities for the affluent. For centuries, silk was so valuable that it was used as a cross-continental currency by Asian and European merchants. Hence, for the bigger portion of human history, the production and ownership of clothes was limited to satisfying people’s basic needs rather than the indulgence of their desires.

Today, we’ve become chronically obsessed with changing our appearance. We’ve become so blinded by the belief that our happiness correlates with our ability to acquire new things that, in just over 60 years, fashion has accelerated into a fast-paced industry, divided into a whopping 52 seasons—in big brands stores, new apparel finds its way into stores in seven-day cycles, and not a year passes without new items of clothing finding their way into our closets.

From a small studio space in a basement in Wedding, STILL garments fashion designer Elke Fiebig is counteracting this wave by committing to fair fabrics and zero waste pattern designs, while captivating consumers with natural dye workshops.

From Berlin to Bangladesh and back again

Elke was intrigued by social good and environmental awareness from a young age. After successfully attaining a degree in Fashion Design from Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weißensee and Designskolen Kolding in Denmark, it was her three-month art residency in southern Germany, coupled with her selection for Goethe Institute’s 12-day cultural exchange program Local International, which emboldened her to carve a path of her own making. As a participant in the project, she traveled to Dhaka, Bangladesh to visit a string of NGOs, production sites and natural dye facilities—an experience she cites as profoundly disillusioning.

“It was really inspiring, but also very shocking. You know that fast fashion exists, but when you see it in real life, it’s much worse than just reading about it or watching it in a film. We went to one production site that was so huge, if we’d wanted to visit all its halls and laboratories, it would have taken us 14 days to explore that site alone. And yet, this was one of the best facilities in the area when it came to workers’ rights. I couldn’t help but think that it must be the worst thing in the world to work there. If you buy a fast fashion t-shirt, even if it’s made of organic cotton under fair conditions, you can be sure that ten people’s sewing went into its making, and each person just did one little seam. You must go crazy if you do the same seam on thousands of t-shirts or pants!”

Witnessing the realities of the industry firsthand fueled Elke’s determination to pursue slow fashion principles in her own creations. Her website outlines her practices and philosophy in detail, which she reinforces with a series of sharp-witted snippets including, “Let’s make it right, rather than less bad” and “It’s not waste until we waste it.”

Slow and steady wins the race

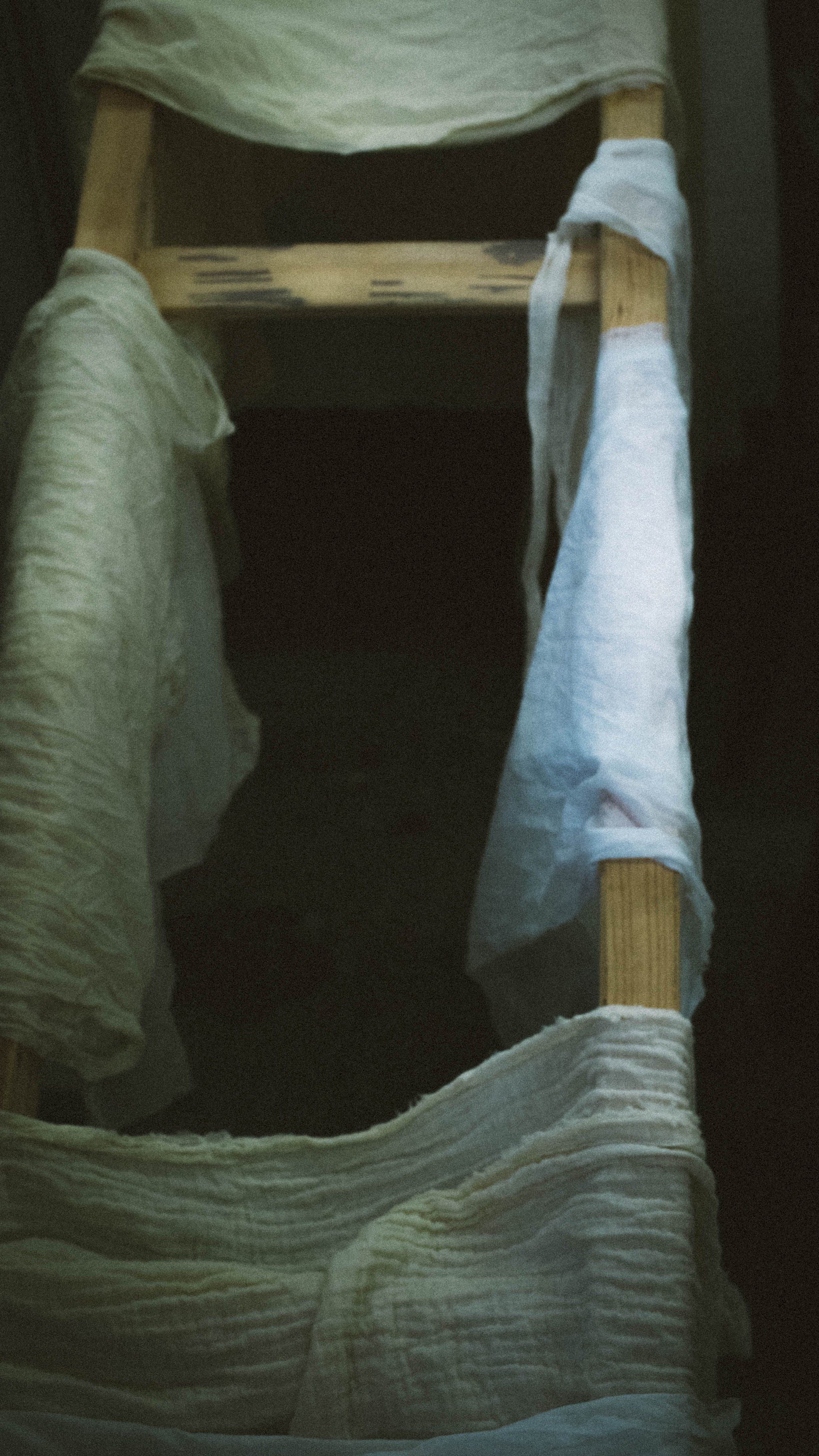

Elke defines slow fashion as such if it opposes industrialised structures, namely, “This idea and entire system that Ford created in which you have these chains. That items are machine made as quickly as possible to reduce prices or to have bigger margins.” As a designer, she chooses to limit the number of garments she creates to what her own two hands can cut, stitch and dye, despite the fact that this means forfeiting the quantity of pieces she can create overall. She admits to having toyed with the idea of reproducing some of her garments in the past, but explains that she quickly abandoned the idea after getting a better grasp for some of the compromises she’d have to make, “If you’ve ever seen large, industrial sewing machines, they’re so fast, it’s crazy. A textile engineer once told me that you can’t use cotton or cellulose-based thread because it gets too hot at the tip of the needle and the thread breaks. Instead, you’d have to use polyester, but that wouldn’t dye. In the end, I don’t want to work like that.”

To date, Elke has produced three collections with her label STILL garments: Edition 0 - 100 & Zero, Edition 1 - Pastels & Variables and Wardrobe Essentials. The red thread that ties them all together: her commitment to zero waste pattern cutting, sustainable materials and natural dyes. The result is a refreshingly conscious series of unique garments.

Elke’s first collection was born from her time in Bangladesh after she ordered a series of off-cuts from one of the companies she had visited during her stay. Initially, she had hoped to attain the oddly shaped scraps they discarded from fast fashion pattern cuttings. Instead, however, she received long pieces of end-of-roll left overs from four different fabrics, forcing her to re-envision her concept and design new patterns from scratch. She smilingly reminisced on the experience, referring to it as “a gigantic puzzle of patterns.”

As a tribute to the fabrics’ source, she dyed the entire collection shades of indigo. “True indigo” is extracted from the leafy parts of a plant native to Bangladesh. Elke wasn’t able to attain this plant in Germany and opted for an indigo pigment instead. In the end, she was still able to achieve excellent results.

Upon examining the end result, it becomes clear that, despite the initial setbacks, she successfully innovated the crafting of functional, ready-to-wear clothing into a stunning series, all the while staying true to her core vision and ideals.

Eliminating pattern waste and cranking up the creativity

Elke’s drive to commit to zero waste stems from one of the fashion industry’s biggest calamities: up to 25% fabric is discarded from a roll after the pattern cutting stage.

Elke describes the dilemma, “The patterns are not made to use as much of the fabric as possible in fast fashion, because time is more valuable than cheap material. Therefore, so much is already thrown away at this stage and consumers never even see that it happens. My idea is to create patterns that don’t create that amount of waste, for example by making use of the negative space of curves as well. Although it means using different ideas to making a garment, it’s actually very close to how clothes were made before the Industrial Revolution when very little was thrown away. The practice still exists in some Asian cultures though, such as with the kimono. But zero waste pattern cutting is also something that can drive you crazy because, especially when you work with vintage fabric, each fabric has a different width. I once bought organic cotton from a relatively large company, ordered the same fabric one year later, and it turned out, it was now 15 cm narrower, and so my pattern no longer fit. It can be complicated to be strict, so I had to learn to be more playful and accept the idea that not all the pieces always have to go into the making of one garment, in other words: that it’s OK to save some left over pieces if I have an idea of how to use it in another garment. But I have to think about that beforehand because it’s usually much harder to figure out how to use it afterwards, so I allowed myself some space for creativity again.”

Spreading the word, connecting with the environment

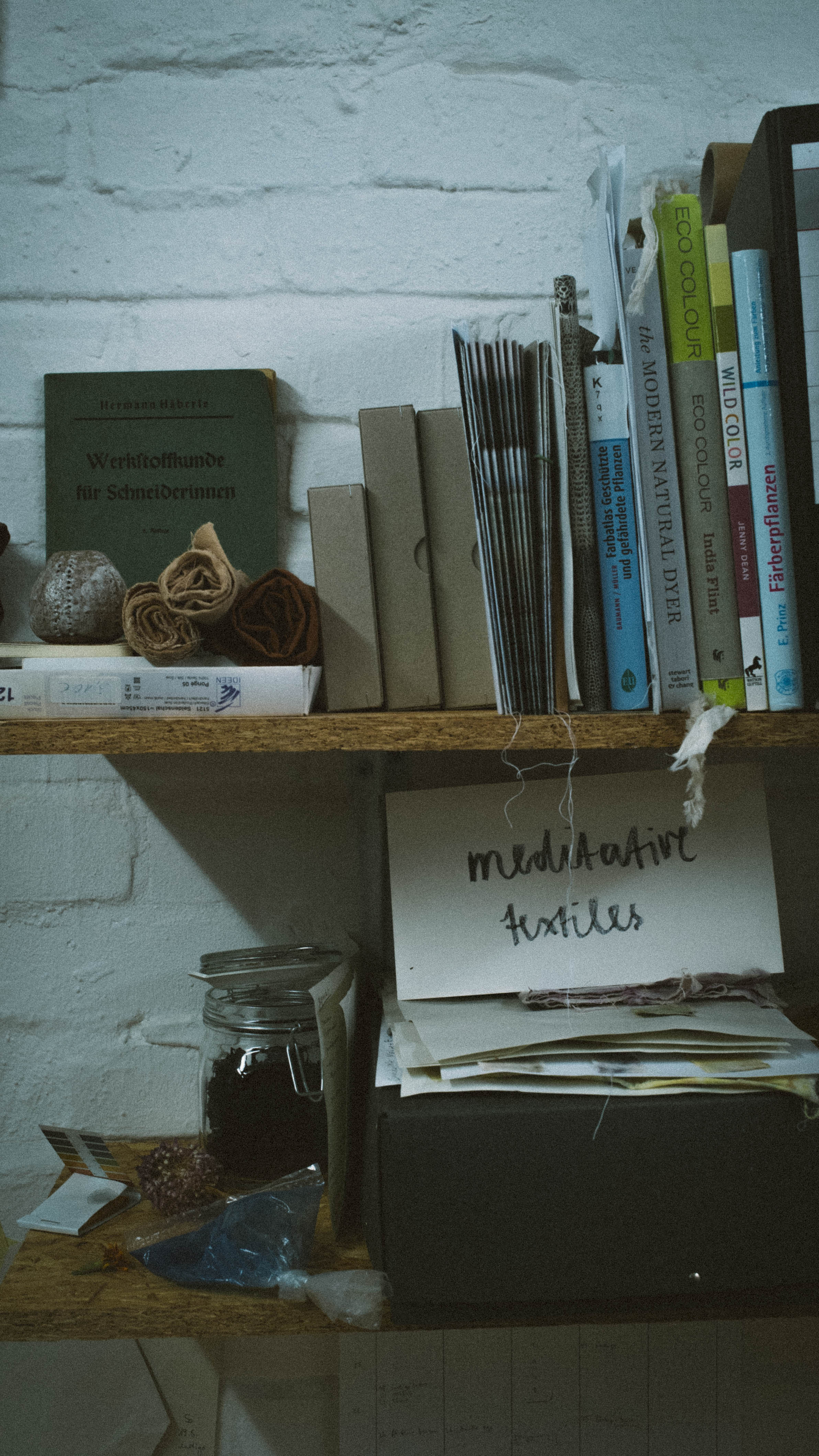

One of Elke’s main motivations for applying for Local International was her curiosity for the art of natural dyeing. She explains, “Bangladesh has a rich craft heritage, but a lot of it is currently struggling or disappearing, so they are trying to find ways to use their traditional techniques and adapt these to Western markets. As an example, we visited one of Ruby Ghuznavi’s organisations—she’s this really amazing woman who brought natural dyes back to life in Bangladesh in the 80’s after they were pretty much gone. In her organisation, they have shade cards, meaning they try and reproduce these colours as closely as possible in their fabrics—an admirable feat as this requires great skill and precision.”

As a designer, Elke is intrigued by the unpredictability nature of the dyeing process. She elaborates on her fascination for the complexities of the craft, “Everything has an influence on the outcome of the colour—the fabric, the plant, at which time of year and where you harvest it, if it was a dry year or a very rainy year. So many factors play their part and it’s really hard to figure out what is doing what.”

In her workshops, Elke seeks to share her knowledge with consumers. She takes participants on their very own journey of discovery. They are given the opportunity to bring their own plants and fabrics to the table as she guides them through the miraculous chemistry of natural colour extraction. She also brings along a wide range of resources, including flowers and plants from her own garden in Weißensee, as well as piles of dyed fabrics samples left over from her 2016 art residency. It was then that the workshop idea first came to her, realising that she did not want to be a designer who made and sold things just for the sole practice of consumption. She felt the need to interact with people on the topic of clothing on a more social level and was inspired to share her knowledge and experience with a wider audience.

Essentially, Elke’s workshops explore the processes of pre-washing, mordanting and dyeing across a variety of themes, such as bundle dyeing, indigo and local plants. “There are very different processes and many solutions,” Elke explains, “but the concept I feel lots of the participants find hard to get into is that you can’t really fix the plant dye after dyeing the fabric—it happens while you do it. I always say that the most important aspect is that it takes time, be patient. Let the things maybe even sit a little longer than you want to and don’t rush it.”

Ageing like a fine wine

Not only is STILL Garment clothing made to last but, as Elke so poetically highlights, each piece ages gracefully.

“I really love hemp and linen fabrics because they become much softer with time. I would like this for myself too, I hope my personality just keeps becoming softer as I grow older. For the dyes, this really depends on which plant was used, how people treat their garments, and where they are living. I once sold a jumper to a lady who spends half of the year in Israel where there’s lots of sun. I don’t know what that piece looks like now, but I would really like to.”

Currently, Elke is working towards finalising her fourth STILL garments collection. As she reflects on 2018, she jokes that, between the creation of her new collection, back-to-back workshops, and the array of part-time jobs she’s been juggling in Berlin’s fair fashion scene, her year has been anything but slow. Moving forward, Elke hopes to find a more balanced pace for herself, while continuing to pursue her passions and share her philosophy and ideals with the world through her creativity and craft.

For more on conscious craftsmanship and natural dye workshops visit stillgarments.com

Text: Maia Frazier

Image: Daniel Eceolaza

Text: Maia Frazier

Image: Daniel Eceolaza